From RROCA-info

ELEANOR, IN BODY OR SPIRIT?

by Paul Tritton, 1986

In 190 BC a colossal marble statue of Nike, Goddess of Victory, was dedicated in the Cabires Sanctuary on the island of Samothrace, in the Aegean Sea. Attributed to Pythocritus, the figure stood poised on the prow of a limestone war galley built in a rocky pool. With her wings lithely outstretched, head held high, and diaphanous gown draped in dramatic swirls, Nike looked as if she had alighted on the ship only moments earlier, to urge the Rhodian fleet to advance in triumph against a demoralized enemy.

More than 2000 years later, Nike became one of the treasures of the Palais du Louvre in Paris. She had not escaped unscathed during the desecration of the art and architecture of ancient Greece. Her torso had been smashed into more than one hundred fragments, needing patient restoration by the Louvre's stonemasons. Her right and left arms were missing, and an even sadder loss was the figure's head. Nevertheless, the statue was an imposing sight when installed on the Louvre's Daru staircase in 1883. For 101 years, Nike of Samothrace has delighted art lovers from all over the world.

Among those who were awed by the way Nike's sculptor had given the figure an impression of majesty and triumphant movement was the first Managing Director of Rolls-Royce Limited, Claude Goodman Johnson. A man blessed with a sensitive nature as well as tremendous business acumen and drive, Johnson sought refuge from the pressures of running the Company by visiting museums and art galleries. His frequent visits to Paris gave him many opportunities to indulge in his appreciation of the arts and spend a few hours in the hushed galleries of the Louvre. When, sometime in 1910, Johnson commissioned Charles Sykes to create an exclusive radiator mascot for Rolls-Royce motor cars, he already had in his mind a picture of the kind of adornment the car should have.

"I want something beautiful, like Nike," he said. "Go and have a look at it."

Charles soon realized that Nike was too majestic and domineering to serve as a pattern for a Rolls-Royce mascot. Johnson had been too captivated by the statue's poise and flowing draperies to appreciate this. But Charles, who had often travelled in the Silver Ghost cars owned by his patron, John Montagu, 2nd Baron Montagu of Beaulieu, knew that a more delicate, sylph-like figure would better express the marque's grace, silence and subtle power. The result, as we all know, was The Spirit of Ecstasy or Flying Lady. And although the resemblance to Nike is only superficial, the winged Goddess of Victory from Samothrace begat an idea from which the world's most distinctive motor car mascot evolved.

It was, of course, entirely appropriate that a goddess should alight on the pediment of Rolls-Royce's Grecian radiator shell. The figurine and radiator gave the Silver Ghost and its successors a distinctive 'image' that no other car manufacturer has been able to emulate. Indeed, the two features complement one another so perfectly that a Rolls-Royce radiator without its Spirit of Ecstasy looks naked. Even though many years have passed since Charles Sykes achieved lasting fame by creating 'the best mascot in the world,' the story of the Flying Lady continues to fascinate admirers of the Rolls-Royce motor car.

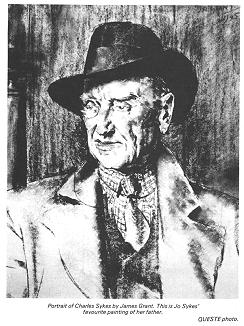

Charles Robinson Sykes was born on 18th December 1875 at 14 Child Street, Brotton, a village in the ironstone mining district that lies between the Yorkshire Moors and Teesside. Because his father, Samual William Sykes and his uncle, Charles Xavier Sykes (S. W. Sykes' brother) were gifted amateur artists, he received every encouragement to take up art as a career.

S. W. Sykes and C. X. Sykes had married sisters by the name of Robinson and their families were close and interdependent. In 1878 they moved to 232 Westgate Road, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, where the two brothers ran a decorating business and made wallpaper and friezes. They prospered, and Samuel was able to send Charles to Newcastle's Rutherford Art College. In his free time Charles was expected to supervise his father's and uncle's apprentices - a responsibility he found irksome.

In 1898 Charles won a scholarship to the Royal College of Art at South Kensington in London, where for three years he studied under such tutors as Arthur Thnmson, M.A., Professor of Human Anatomy at Oxford University and Walker Crane, the book illustrator. At the college, Charles developed his drawing and painting abilities, studied sculpture and made experimental castings in gold, silver and bronze. He thus became an artistic 'all rounder' and assured himself of a varied, exciting and by-and-large remunerative career. His teachers at the Rutherford, and his parents, had hoped that after completing his education he would settle in Newcastle and help train the city's up and coming craftsmen. But Charles had acquired a taste for London life, and was soon working and living among the capital's artistic community - thanks to the inability of one of his first clients to pay his bills.

The client was Cummings Beaumont, publisher ot a Northumbrian county magazine, who commissioned Charles to produce some sketches. Beaumont was so short of cash that he was unable to pay Charles. Instead he offered to introduce him to John Montagu, who had taken a suite of offices overlooking Piccadilly Circus and was gathering together a creative team to launch a glossy weekly magazine called The Car Illustrated.

The year was 1902, when motoring mania was sweeping through London society, thanks largely to the efforts of the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland, then in the process of moving its headquarters to 119 Piccadilly. The organizing genius behind the Club was Claude Johnson, its first fulltime secretary. Two years later, Johnson became a partner of the Hon. Charles Rolls and Henry Royce. Johnson took a close interest in Montagu's new magazine and recognized the talents of its gifted young artist from Tyneside, who became a regular contributor of illustrations and cartoons.

The publication relied on a very high standard of design in order to appeal to an up-market readership. Charles' contributions, which ranged from cover artwork to fashion drawings, created the 'image' Montagu wanted his publication to achieve. Within a few years the magazine began printing illustrations in full colour. For Charles, this innovation provided totally new opportunities. His special full-colour illustrations for the magazine's Christmas issues havc a charm and style of their own and combine what was then new technology with what was to become a recurrent theme in his work - winged goddesses (often carrying wands or flaming torches) riding on chariots or, as often as not, motor cars!

His Christmas 1906 front cover, the original oil painting of which hangs in the office of Edward Montagu, the present Lord Montagu, at Palace House, Beaulieu, is an especially brilliant example of Charles' classical imagery. It was entitled The Spirit of Speed. Curiously, this was the name given to the Rolls-Royce mascot some years later, only to be discarded in favour of The Spirit of Ecstasy. Two other works in the same style now belong to Dorothy Hayter, widow of Gordon Hayter, who worked with Charles on The Car Illustrated. In Jo Sykes' opinion, the model for the winged figures in both these works was Eleanor Thornton, who had been Johnson's secretary at the Automobile Club until 1902, when she became John Montagu's personal assistant.

Miss Thornton - 'Thorn' or 'Thorny' to her friends - was Charles' favourite model, posing for many of his paintings, sketches and sculptures. Although he began his career as a graphic artist he very quickly found opportunities to use the casting skills he had acquired at college. Once again, Montagu was his patron and the occasion that put his talents as a sculptor to their first major test was the 1903 Gordon Bennett Motor Race.

Since 1900, teams representing national motor clubs had competed in an annual road race in France in which the prize was a Silver trophy presented by the American newspaper tycoon, James Gordon Bennett. Long distance road races had been regular events on the Continent since 1894 but by the turn of the century only two British drivers had managed to acquit themselves reasonably well - Charles Rolls and John Montagu. In 1899 they took second and third prizes in the Tourist Class of the Paris to Ostend Race, and Rolls went on to win the Tourist Class in the Bordeaux to Biarritz Race.

The 1903 'Gordon Bennett' held in Ireland attracted greater public interest than previous events in the series, and for the first time four countries were represented - Britain, France, Germany and the U.S.A. Hitherto just one trophy had been at stake, awarded to whichever club sponsored the winning driver, but this time Montagu donated a second trophy, for the club achieving the best aggregate performance.

The Gordon Bennett Team Trophy, as it was called, was designed by Charles Sykes and depicted a female figure, cast in silver, holding a silver-winged bronze motor car. "Mr. Sykes has combined originality of design with beauty of conception," said Montagu. It is quite likely that Eleanor Thornton was the model for the figure. Camille Jenatzy of Germany won the Gordon Bennett Trophy; Montagu's trophy went to the French team, which took second, third and fourth places. The British team gave a disappointing performance and S. F. Edge was disqualified because someone gave his car a push to help it move away from a control point. He did, though, go on to enjoy further successes in races and trials. The achievements ot Edge and his Napier at Brooklands are legendary, and it was Charles Sykes who desiqned the medallion presented to Edge to commemorate his epic drive in June 1907, when he covered 1581 miles 1210 yards in 24 hours. It shows a drowsy Edge and his slumbering mechanic being beckoned onward by one of Charles' familiar goddesses holding a laurel wreath.

Because so much of his work had to satisfy the demands of motoring enthusiasts, it was inevitable that Charles Sykes combined the disparate worlds of Greek mythology and Edwardian motoring in many of his commercial creations. But he was also devoted to the fine arts. Two commissions from John Montagu helped Charles apply his talents in this direction: he painted a triptych for Beaulieu parish church, and designed the bronze Madonna and Child still to be seen in a niche at the Montagu family's home, Palace House - formerly Beaulieu Abbey's Great Gatehouse. Legend maintains that until the Dissolution the niche contained a Golden Madonna. Few visitors to Beaulieu realize that the bronze figure there now was designed by the creator of The Spirit of Ecstasy mascot.

Bronzes became one of Charles' specialities and eventually he achieved every sculptor's ambition by having his work exhibited at the Royal Academy. One of these was a figure entitled A Bacchante, shown at the RA and the Paris Salon. Jo Sykes who remembers seeing Eleanor Thornton posing in her father's studio on many oceasions, notices a strong resemblance between Bacchante's face and figure and that of Miss Thornton. She also identifies a Junoesque figure made about the same time as definitely being a bronze of Miss Thornton. Two examples of this have been traced. One belongs to Mrs. Hayter and was previously the property of Gordon Hayter's first wife, Rose Thornton, Eleanor's sister. It probably originally belonged to Eleanor herself, passing to Rose after Eleanor was drowned in 1915 when the ship on which she and John Montagu were travelling was torpedoed by a German U-boat. The other bronze of Elpanor belongs to the family of the late Joan Thornton, daughter of Eleanor and John Montagu.

Bacchante and the Eleanor Thornton bronze are contemporary with two other Sykes bronzes with a fascinating history: The Sybarite (circa 1908) and Phryne. The Sybarite, for which Eleanor Thornton posed, depicted a long-haired naked woman, standing on a cushion. Because it failed to impress the arbiters of what was considered to be artistic good taste Charles cut her hair short, replaced the cushion with a round base, and renamed the figure Phryne. The only example we have been able to trace belongs to Cynthia Sheerman, daughter of the late Herbert anf Myra Barder, two friends of the Sykes family.

Charles and his wife Jessica, whom he married in 1903, stayed at Beaulieu as guests of John and Lady Montagu on several occasions. They became close friends of the Montagus, to the extent that their daughter Jo, born in 1908, was baptised in Beaulieu parish church. During his visits Charles saw the latest Rolls-Royce cars at close quarters, since from 1908 onwards John Montagu regularly purchased new Silver Ghosts. Charles also had many opportunities to ride in Montagu's cars, and soon produced a series of paintings of various Silver Ghosts in their natural habitat, several of which were published in The Car Illustrated.

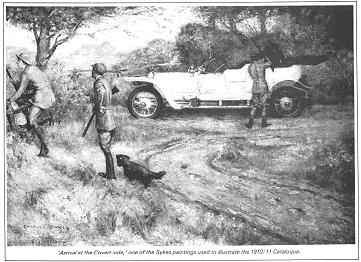

Montagu and his friends devoted much of their leisure to shooting, fishing and party-going, and one of Charles' earliest paintings of motoring life, preserved in the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu, is a charming study of John Montagu and his friends arriving for a day's shooting in one of Beaulieu's forests. The car in the picture is Montagu's first Silver Ghost, a type 70, chassis number 60751.

In complete contrast, but equally evocative, are two paintings entitled A Nocturne in Blue and A Ghost Overtaken by the Dawn. The first shows a Silver Ghost limousine arriving at night at a country house. In the second, the limousine and its sleepy passengers head homewards along a deserted road as the first glow of daylight awakens the surrounding countryside.

It was fortunate that the John Montagu encouraged Sykes came to capture on canvas the style and beauty of the Silver Ghost, because when in 1909 Claude Johnson decided to produce Rolls-Royce's most lavish brochure to date, he had no difficulty in deciding who should produce the artwork for its colour plates: Charles Sykes.

The 80-page 1910/11 Catalogue is a coveted document among Rolls-Royce enthusiasts, containing a wealth of information on the Silver Ghost's mechanical features and trials achievements, and some fascinating illustrations. The production is given its final seal of quality by six Sykes oil paintings of Rolls-Royce cars. Entitled Arrival at the Opera, Arrival at a Country House, Arrival at the Golf Links, Arrival at the Meet, Arrival at the Convert-side and Arrival at the Salmon Stream, they were assigned to Rolls-Royce between June 1909 and April 1910. At this time the Company also acquired the copright of several of Charles' other works. These comprised oil paintings showing the mode of transport used when travelling to the opera, a country house, a hunt and a golf course in 1808, plus A Rolls-Royce car at Dusk, A Rolls-Royce arriving at the top of a steep hill and A Rolls-Royce car in a snowstorm.

Until the last war at least seven of the paintings Sykes assigned to Rolls-Royce were still to be seen in the office of the Company's Chairman, Lord Herbert Scott (a cousin of John Montagu) at 14/15 Conduit Street, London.

Soon after completing his work for the catalogue, Charles embarked on the most famous commission of his career: the creation of The Spirit of Ecstasy. This has become one of the most legend-ridden episodes in the historv of the Rolls-Royce marque, the principal stories being that the idea of sculpturing a delicate fairy-like goddess occurred to Charles whilst he was travelling in one of Montagu's Silver Ghosts; and that Eleanor Thornton was his model.

There can be no doubt that the story of Charles' ride in Montagu's Silver Ghost has a basis of truth. By late 1910, when Claude Johnson decided he wanted a mascot, Charles had enjoyed many journeys in Montagu's cars. The crucial, mascot-inspiring ride is said to have been made in the south of France, but so far as is known Charles never accompanied Montagu to France. The road from London to Beaulieu is probably where, in Jo Syke's words, Charles became "Very impressed with the smoothness and speed of the car, and imagined that even so delicate a thing as a fairy could ride on the bonnet without losing her balance."

Charles' impressions must have been built-up during a series of journeys, since his visits to Beaulieu and his work for the 1910/11 Catalogue had given him many opportunities to ride in Silver Ghosts. He also accompanied Montagu to Northampton to attend a luncheon celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Automobile Club's 1000 Miles Trial. This event took place in April 1910, when Montagu was still running his type 70, whereas by the time Charles was working on ideas for the Rolls-Royce mascot, Montagu had taken delivery of a new Silver Ghost Barker open tourer, chassis no. 1404. Bill Morton, an authority on early Rolls-Royce cars, has described the Type 70 as a bad advertisement for the marque because it had "clattery" overhead inlet valves and was less tractable than the standard Ghost. Therefore, 1404 would have given Charles a better impression of smoothness. If any one Rolls-Royce inspired the idea of a fairy-like figurehead, it was 1404.

Although he rejected Claude Johnson's idea of a Nike-like figure, Greek mythology was not far from Charles' mind as he sketched and modelled various ideas for the mascot. By now he had obtained plenty of practice at drawing scantily clad winged goddesses, and at sculpturing nude female figures. He would therefore have had no difficulty in creating the figurine he had in mind, though he would have needed the services of a model to help him perfect details of the mascot's pose. Jo Sykes remembers Eleanor Thornton as a strong, vigorous, statuesque woman - rather like Nike in many ways - and not the floating delicate form embodied in The Spirit of Ecstasy. So although Eleanor probably posed for the specific purpose of helping Charles develop his design for the mascot, it is not in its finished form a figure of her or any real person.

Nevertheless, the story that Eleanor was the model for the mascot spread quickly among her friends and acquaintances. Reggie Ingram, John Montagu's doctor, who know her well, once said of the mascot: "They shouldn't have put Eleanor's head on it." Another believer was Gordon Hayter, who attended Eleanor and Rose Thornton's parties in their apartment at The Pheasantry, an artist's colony in Chelsea. Gordon was one of Fleanor's many admirers, and when Rose died he inherited examples of Charles Sykes' works that had originally belonged to Eleanor. Among them were sketches of Eleanor, a woodland scene signed 'Charles Sykes to Thorny' and a solid silver Spirit of Ecstasy. This had at one time been an ornament in the Thornton sisters' apartment, and was probably a gift from Sykes to Eleanor. Unfortunately it was stolen from Mrs. Hayter's home about 17 years ago.

Those who believe that Eleanor was the model for The Spirit of Ecstasy also support their case by citing a photograph in the Montagu archives, showing her on board Silver Ghost 1404. The photographer has carefully ensured that both the figurine and Eleanor are included in the picture, almost as if to say "this is the mascot, and the car and the lady who inspired it." The picture was probably taken soon after 16th March 1911, the date on which Sykes assigned to Rolls-Royce his rights and interests in what was still called The Spirit of Speed.

By then, though, the name by which the figurine would become popularly known had emerged in a letter from Rolls-Royce to John Montagu, in which the Company explained that it sought a mascot that would convey

"in the model of a little lady, the spirit of the Rolls-Royce - namely, speed with silence, absence of vibration, the mysterious harnessing of great energy, a beautiful living organism of superb grace like a sailing yacht. Such is the spirit of the Rolls-Royce, and such is the combination of virtues which Mr. Charles Sykes has expressed so admirably in the graceful little lady who is designed as a figurehead of the Rolls-Royce."

The letter added that when Charles designed the "graceful little goddess" he had in mind

"the spirit of ecstasy, who has selected road travel as her supreme delight and alighted on the prow of a Rolls-Royce car to revel in the freshness of the air, and the musical sound of her fluttering draperies."

Rolls-Royce agreed that Charles would be the sole supplier of the mascot, and production was organized from the Sykes family's maisonette above Herbert Barder's furriers shop at 193 Brompton Road, West London. It was in his studio there that Sykes designed The Spirit of Ecstasy and sculptured the original model.